The Procrastination Trap

Procrastination's diet primarily consists of last-minute assignments. It likes the assignments that are hastily put together the night before.

It loves all-out panic study sessions right before an exam. It has a particular taste for anxious writing and shortcuts in work.

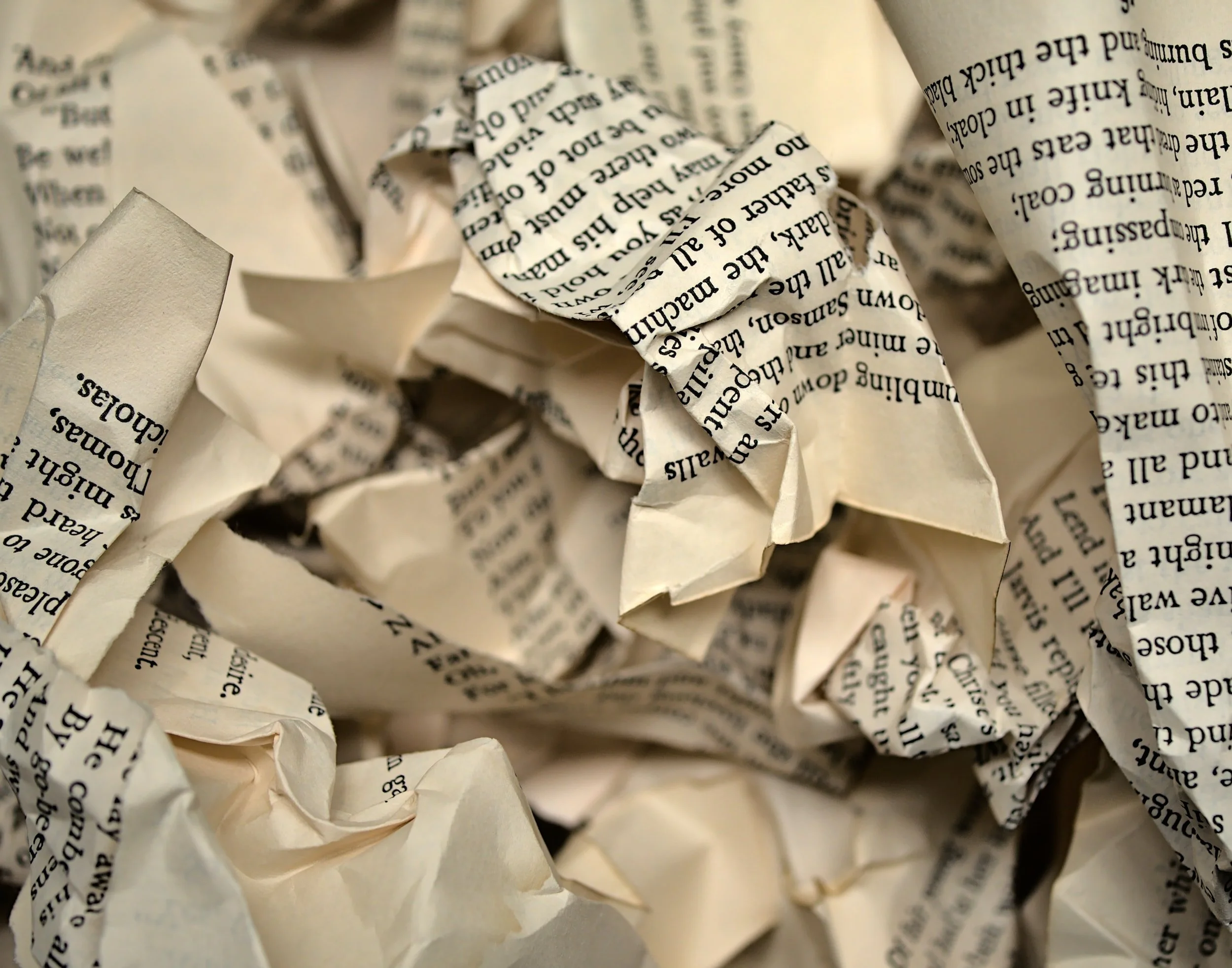

You can see procrastination at the end of any school semester, feeding on long-lost assignments and last-minute study sessions. Procrastination will continue it’s destruction until the assignment is crumpled up and thrown in to be graded. By then, it is often too late, and the problem has become too big. Procrastination doesn’t care about deadlines and due dates.

However, before procrastination was this big monster, it started out small.

It was once a cute little problem; you fed it a little here and there. You say to yourself: Why not start that assignment tomorrow?

At this point, you have so much time before it is due.

Little did we know that this problem was getting bigger and bigger, becoming all the wiser about what it needed to do to create that perfect last-minute panic.

In the Start

Procrastination has those cute eyes. It stares up at you when you have lots of time. It knows you have lots of time. It knows that, at the beginning of assignments, students tend to overestimate the time they have and underestimate the time it will take to complete the assignment (Buehler, Griffin, & Ross, 1994; Ferrari & Díaz-Morales, 2007).

This makes you think that the weeks before the assignment can be filled with other activities. You think maybe you have too much time. You wouldn’t want to get started too soon, would you?

It tells you,

This assignment looks easy; it’ll only take a few days to get it done.

It builds your confidence and pumping you up.

You feel good. You feel in control.

In your mind, this assignment is already done.

As time goes on, you approach the last couple of weeks, and nothing is done. If anything, you have forgotten your initial ideas and the relevant lessons for preparing for it.

Procrastination sees this and knows all too well what the next step is to get that final last-minute feast.

It tells you,

You’re starting to feel stressed. That’s good; you work best under stress!

You start to feel confident again.

You begin to erroneously believe that you work best under stress and pressure (Sirois & Pychyl, 2013;Tice & Baumeister, 1997).

You say to yourself “those who are under stress produce the best work.” You’re the type of person who enjoys the thrill of getting close to the deadline and handing in the paper last minute. At least, that’s what procrastination has tricked you to believe.

The Final Week

This is crunch time, and you only have a few days left.

Friday at 5 p.m. is the deadline. At 5:01 p.m., it is too late and you will not be able to hand it in.

As you look back at the time you had, you start to feel upset. Why did you waste all that time? You worked out, hung out with friends, watched television—all of which are great things but you failed to schedule in a little time each week to get this assignment done.

You sit down to work on the assignment, and this frustration comes back.

As you start to write, procrastination comes out and knows exactly what to say next.

Doing this assignment in your current state is not going to be any good. However, I know tomorrow you’ll feel much better.

You then put down the pencil and take it easy. You tell yourself “tomorrow I will get to it and complete it.”

The LAST-MINUTE CRUNCH

By now, the fog has cleared, revealing the reality.

You have no time left for the assignment, and you must piece together what you can with the limited time left.

Procrastination knows the job is done.

Another success for procrastination, and it has moved on to the next student and assignment due.

Procrastination is a common issue among students in learning. It is a frustrating phenomena that is defined as an intentional delay in starting and completing a task that you know you should and being worse off as a result (Steel, 2007). This behavior is highly prevalent in educational settings and is a frequent concern among students.

The good news is that extensive research exists on what procrastination is and how to cope with it.

Below, I’ve listed a number of resources to help you learn more about procrastination and methods for coping with this specific issue.

Disclaimer: A lack of motivation can arise from various underlying causes. If you are concerned, it is important to seek professional help tailored to your specific needs. Consider consulting your family doctor about any physiological issues or scheduling an appointment with a local therapist to discuss your struggles.

Resources

https://www.procrastination.ca/: This website was created by Dr. Timothy Pychyl and offers a wealth of information on procrastination.

Solving the Procrastination Puzzle: A Concise Guide to Strategies for Change: This book by Dr. Timothy A. Pychyl provides practical strategies for understanding and overcoming procrastination.

The Procrastination Equation: How to Stop Putting Things Off and Start Getting Stuff Done: This book by Dr. Piers Steel explores the psychological and neurological factors contributing to procrastination.

Eat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less Time: This book by Brian Tracy presents a simple yet effective methods for prioritizing tasks and overcoming procrastination.

References and Selected Relevant Academic Research

Buehler, R., Griffin, D., & Ross, M. (1994). Exploring the "planning fallacy": Why people underestimate their task completion times. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(3), 366–381.

Ferrari, J. R., & Díaz-Morales, J. F. (2007). Procrastination: Different time orientations reflect different motives. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(3), 707-714.

Pychyl, T. A., Lee, J., Thibodeau, R., & Blunt, A. (2001). Five Days of Emotion: An experience-sampling study of undergraduate student procrastination. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 15(5), 239-254.

Sirois, F., & Pychyl, T. A. (2013). Procrastination and the priority of short-term mood regulation: Consequences for future self. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7, 115-127.

Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65-94.

Tice, D. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (1997). Longitudinal study of procrastination, performance, stress, and health: The costs and benefits of dawdling. Psychological Science, 8(6), 454-458.

Yerdelen, S., McCaffrey, A., & Klassen, R. M. (2016). Longitudinal examination of procrastination and anxiety, and their relation to self-efficacy for self-regulated learning: Latent growth curve modeling. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 16(1), 5-22.